Power to the People: The Most Inspiring Protest Songs of All Time

This article appeared in the NY Observer on 12/13/16 - Here it is without ads or Jared Kushner - who bought the paper and fired everyone...

The original title of this piece was:

“Power to the People” - A (Partial) Protest Playlist for Topsy-Turvy Times

Whether funny or blood boiling, protest songs have a way of getting under our skin. They come in all styles - from the earnest folk anthems of Joe Hill and Woody Guthrie to Bob Dylan’s sharply articulate finger-pointing tirades, to the funky “Message Music” of Sly Stone and Gil-Scot Heron, to inner-city hip-hoppers spitting truth over a hammering beat. Whether topical or enduring decades, these songs are designed to provoke a response, be it thought or to take action. Below is a partial playlist to serve as a sonic baluster for the current volatile political climate now engulfs us all.

Sixty-six years ago this December, the legendary Okie troubadour Woody Guthrie rented an apartment near Coney Island owned by Fred C. Trump, father of the current president elect. A tireless champion of the poor and powerless, Woody’s songs boldly stood up to bigots and fascists a like. Guthrie name-checked his notoriously racist landlord in two songs – “I Ain’t Got No Home,” and “Old Man Trump,” in which he spelled his feelings out loud and clear: “Old Man Trump knows just how much racial hate he stirred up in the blood-pot of human hearts when he drawed that color line here at his eighteen-hundred family project.” A recent remake of Woody’s song recorded by Ryan Harvey with Ani DiFranco and Tom Morello (released in June, 2016) does Guthrie proud.

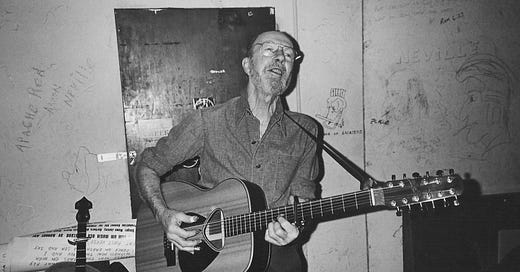

Pete Seeger, backstage Lone Star Cafe NYC 1985 - photo by John Kruth

Inspired by the Ukrainian folk song, “Koloda-Duda,” Pete Seeger’s melancholy “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” (recorded by both the Kingston Trio and Peter Paul & Mary) stood as a gentle, yet stoic anthem of peace in the face of the seven million tons of bombs dropped on Vietnam by the United States. “When they will they ever learn?” Seeger wondered, to which Bob Dylan soon replied “The answer my friend is blowin’ in the wind.” Dylan’s portfolio of potent protest songs included “The Times They Are A Changing” and “God on Our Side,” which adroitly articulated the mounting fears faced by his generation – from the Cuban Missile Crisis and to fearing the draft. Taking a stand against what reggae singer Peter Tosh dubbed “the shitstem” was all in a day’s work for the young scruffy folk sage. “How much do I know to talk out of turn? You might say I’m that I’m young, you might say I’m unlearned,” he snarled over a droning minor chord. Words blast from Bob’s mouth like bullets. But he needs no gun. His mercurial mind was his weapon, a rocket launcher taking dead aim at Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara one of the prime strategists of the Vietnam War.

One cannot evoke Dylan’s radical reveries without failing to mention the “staggering” (Dylan’s description) Joan Baez. “Joan’s fierce dedication to peace was incredibly powerful even at age eighteen,” recalled her old friend Betsy Siggins-Schmidt, founder of the Folk New England Archive. “Her version of [Alfred Hayes and Earl Robinson’s haunting ballad of labor activist/martyr] ‘Joe Hill’ is simple and direct - no frills, very much like Joan, who was always completely comfortable with making us think and feel. She knew so much about the world, its inequality and poverty.”

Joan Baez backstage Boston Symphony Hall, 1984 (photo by John Kruth)

Following the April 4th 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, inner cities across America, from Newark to Watts burst into flames. By May student riots had erupted in Paris when twenty thousand protesters (a mix of high school and college kids, teachers and workers) marched at Sorbonne University, where they were met with tear gas and beaten with batons before being thrown into jail cells. By month’s end the protests nearly ground General de Gaulle’s government to a halt. Mick Jagger claimed to have been inspired by the Left Bank insurrections while writing “Street Fighting Man,” over an urgent, grinding guitar groove, courtesy of Keith Richards, that boldly declared the time was right for “a palace revolution.”

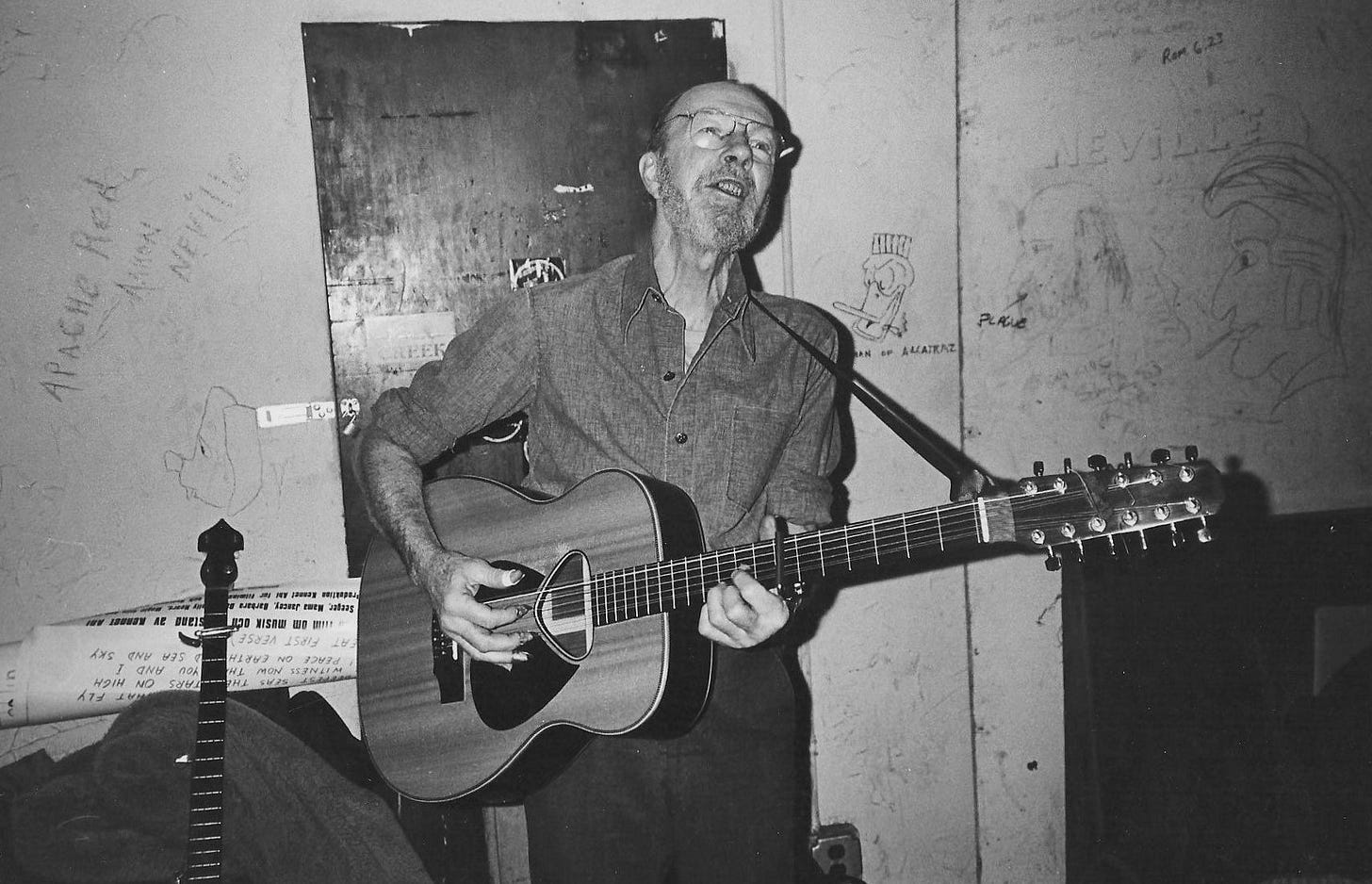

Whether inspired by Yoko Ono, Jerry Rubin or David Peel, John Lennon, upon his arrival in New York in 1971 suddenly got his radical on. Through-out most of the sixties the Beatles had remained aloof on matters of war, poverty and human rights (most likely due to their manager Brian Epstein’s tight control over their image). Love, beginning with the girl/boy variety and later, the universal power capable of saving the world (along with the occasional sly message about getting high) had been the Fab’s domain. But now John, who just a few years earlier had been chauffeured around London in a paisley painted Rolls Royce, had traded in his psychedelic Silver Cloud for some khakis and a bullhorn. The working class hero and his Japanese conceptual artist wife, were suddenly crowing “Power to the People,” and recording Some Time In New York City, a double album filled with simple three-chord agitprop anthems about Angela Davis, the Attica State jail riots, and atrocities in Northern Ireland.

John & Yoko - Two Virgins fighting for peace & love

“Wake Up Niggers” was a startling message from Harlem’s proto-rap group, the Last Poets who best portrayed the grim atmosphere and overwhelming hopelessness that pervaded America following MLK’s death. Featured on the soundtrack to the 1970 film Performance, (which starred Mick Jagger as a debauched and forgotten rock-star) the Last Poets’ “Wake Up Niggers” exploded like a Molotov cocktail in the consciousness of anyone who came within earshot of the record. While the song received zero airplay, the movie soundtrack, which featured the Rolling Stones and Ry Cooder was the perfect vehicle for the Last Poets to get the word out. Over foreboding conga drums and a chorus chanting “Wake up, wake up,” the message came across loud and clear - the time had come to stand up and demand equal rights, as Malcolm X proclaimed, “By any means necessary.”

Initially Motown producer Berry Gordy tried his best to keep a lid on the dissent brewing amongst his artists until he realized the record-buying public hungered for something beyond the cute, catchy love songs and smooth dance steps his label had to offer.

Whether inspired by Dylan or Sly & the Family Stone’s joyous jam of equality and brotherhood, “Everyday People,” the Supremes, in November 1968, suddenly dropped their hair spray canisters and the sticky sentiments of “Baby Love” and addressed the problems faced by young unwed inner-city mothers in “Love Child.”

The next politically-tinged missive from Motown hit the street in February ’69 with the Temptations’ funky drug-induced daydream/nightmare “Cloud Nine,” followed by the suave lady-killer, Marvin Gaye who began asking troublesome questions about the Vietnam War and the state of the ecology on his 1971 brilliant album What’s Going On? Although coming late to addressing daily issues confronting African/Americans, Stevie Wonder’s 1973 mini-opera “Livin’ For the City,” is a powerful snapshot of ghetto life.

Down in “Trenchtown,” as Kingston, Jamaica, is known, the Wailers (Bob Marley and Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingstone) released Catch A Fire in 1972, a hard-groovin’ reflection of life in the “Concrete Jungle.” Their seminal debut also featured the ominous “Slave Driver,” which warned the island’s long-time oppressors, the British colonizers that “the tables are turning.” The Wailers’ follow-up 1973 album Burnin’ featured the reggae anthem “Get Up, Stand Up,” inspiring people world-wide to “stand up for [their] rights.”

With “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” Gil Scott-Heron, the radically articulate street poet/proto-rapper reminds us, to paraphrase Dylan in “Blowin’ in the Wind” that we cannot “turn our heads and pretend that we just don’t see.” First recorded as a spoken-word piece in 1970 (and later released with jazzy flute and funky beats) Gil-Scott assured us, the day will come when everyone will have to fight for what they believe: “You will not be able to stay home brother, you will not be able to plug in, turn on and cop out.”

“That’s ‘The Sound of da Police’ Whoop! Whoop! That’s the sound of the beast,” chanted KRS-One (known to his mother as Lawrence Parker). “The real criminal are the C-O-P,” he growled as the 1993 video flashes images of African-Americans pulverized by the forceful spray of firehoses turned on them during the Alabama civil rights riots in the 1960’s. “My grandfather had to deal with the cops,” KRS-One shouts, reciting a litany of abuse that stretches back to his great-grandfather and great, great grandfather. “When’s it gonna stop?” he begs, as images of world-wide riots rage behind him. KRS-One, whose name is an abbreviation of the blue Hindu flute-playing god, Lord Krishna (also spelled KRSNA) has, with the help of his spiritual practice, always tried to take the high road, while helping his fans to rise above the violence and chaos of the ghetto.

There comes a time when deteriorating social conditions no longer allows musicians to keep writing what Steve Earle calls “chick songs.” And having been married seven times, Steve knows something about “chick songs.” But with the release of his 2004 album, The Revolution Starts Now it was clear that Earle felt the time had come to take a stand. The collection of songs were written and recorded in a matter of days as an urgent telegram to the American people to wake up and reclaim what’s left of our dwindling democracy. Earle employed a straight-ahead, grindin’ rock band (The Dukes) to drive home his populist message with fuzz-drenched guitars that, recalled many of the great sixties bands like Credence Clearwater Revival and the Velvet Underground. The album, a rockin’ political hot potato, captured a similar spirit to Neil Young’s strongest political statement, “Ohio,” which was written and recorded live on the same day.

Earle’s “unapologetic leftist” message music, particularly in “John Walker’s Blues,” a moving ballad about John Walker Lindh, (from his 2002 release Jerusalem) about the Marin County teenager who went looking for something to believe in beyond the vapid lifestyle he found in Rolling Stone and MTV, and became a Muslim fundamentalist, fighting in the Jihad, brought a storm of controversy down on Earle, as the press immediately branded him “a musical Michael Moore” for his sympathetic view of the lost kid turned traitor.

“The reason that Michael Moore scares the living fuck out of people is because he is not an elitist,” Steve countered. “He comes from working people. He’s not spouting political theory on an abstract level.”

“I totally believe Pete Seeger when he said that all songs are political, because lullabies are political to babies,” Earle added. “We’re living in politically charged times, so these last few records I’ve made are really political. But when I die, if you do the math you’ll probably find I have written more songs about girls than I did politics.”