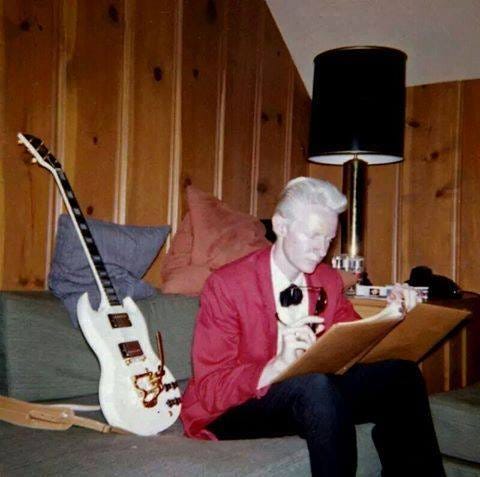

Johnny Winter’s Electric Firebird Blues

A reprint from Fretboard Journal a few years back commemorating the great, singular guitarist on the day of his passing in 2014

From his unique appearance to his remarkable chops, there was nothing typical about John Dawson Winter III. “Musical from birth,” as his mother Edwina once described him, Johnny was raised in Beaumont, Texas, in a home where his father, John Jr. picked banjo and blew saxophone, and his mom played piano. Growing up, Johnny and his younger brother Edgar, heard plenty of big band, Texas swing and country music emanating from the family radio. His first musical crush came at age five with the clarinet, but the family dentist, concerned about a substantial overbite suggested the boy take up another instrument. Johnny soon switched to the ukulele but his father, unable to name another famous uke strummer beyond Arthur Godfrey persuaded his son to try his hand at the six-string.

Singing in two-part close harmony the Winter brothers worked up a repertoire of country tunes and appeared together, to win local talent shows and perform together on live on the radio. But although they loved each other like brothers, they also fought like brothers, and Johnny made it clear from the get-go that they would not follow in Don and Phil Everly’s footsteps.

By the time he’d turned fifteen, Johnny had already become a professional musician, forming a slew of bands with monikers from Johnny and the Jammers to the Black Plague. In 1960 Winter cut his first sides - the Chuck Berry inspired “School Day Blues” and a lumbering Fats Domino style ballad titled “You Know I Love You” for the Houston-based Dart Records. Just in the ninth grade at the time, Johnny sang and played guitar, while Edgar, two years younger, in seventh grade, hammered the piano keys ala Jerry Lee Lewis.

Although hardly inconspicuous, Johnny, an underaged albino would not be deterred from sneaking into Beaumont’s Black Raven Club to see Muddy Waters and Bobby Blue Bland and eventually sit in with B.B. King. Hungry for any new musical experience, Winter even played bass for itinerant country legend George Jones at a gig in Vidor, Texas in 1962.

In the early 1960’s a burgeoning generation of young white guitarists from America and the UK (that included Brian Jones, Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, John Hammond and Danny Kalb) had become obsessed with and passionately devoted to learning every nuance of the indigenous music of the Mississippi Delta. Originally these interlopers were viewed with skepticism and humor by the very men who created the music. “Can white men play the blues?” seemed to be the great conundrum of the day until an albino guitar prodigy from Beaumont, Texas put an abrupt end to the nagging question.

For Winter, playing the blues was simply a natural expression of who he was. “There never seemed like there was a problem with me… I never stopped to think are you supposed to do this or not,” he said, sitting beside B.B. King, as the two men jammed and talked with their host Felica Jeter, on CBS Nightwatch back in the early 80’s.

Johnny’s first album, The Progressive Blues Experiment was radical stuff. Winter played with genuine fire and looked… well, strange on the album cover, under a kinetic storm of white hair, staring at his own reflection on the back of his National Steel guitar.

Winter’s repertoire featured a mix of Muddy Waters, B.B. King, and Sonny Boy Williamson tunes, as well as a handful originals. Cut with the help of his steady rhythm section - drummer “Uncle” John Turner and bassist Tommy Shannon for the small, Austin-based Sonobeat label in 1968, Winter quickly captured the collective imaginations of a young generation of rock fans coast-to coast after Larry Sepulvado and John Burks in a Rolling Stone article dated December 7 1968, described him as “a 130-pound cross-eyed albino bluesman with long fleecy hair playing some of the gutsiest blues guitar you have ever heard.” Although he article also mistakenly identified Edgar as his twin brother, it worked wonders for Johnny’s career.

Steve Paul, who ran one of hippest clubs in Manhattan – The Scene (located in a basement on 46th Street and 8th Avenue) immediately flew down to Houston to meet Johnny and began opening doors for one of the only guitar-slingers on the planet who could stand beside Jimi Hendrix or Mike Bloomfield who dubbed him “the best white blues guitarist [he’d] ever heard.”

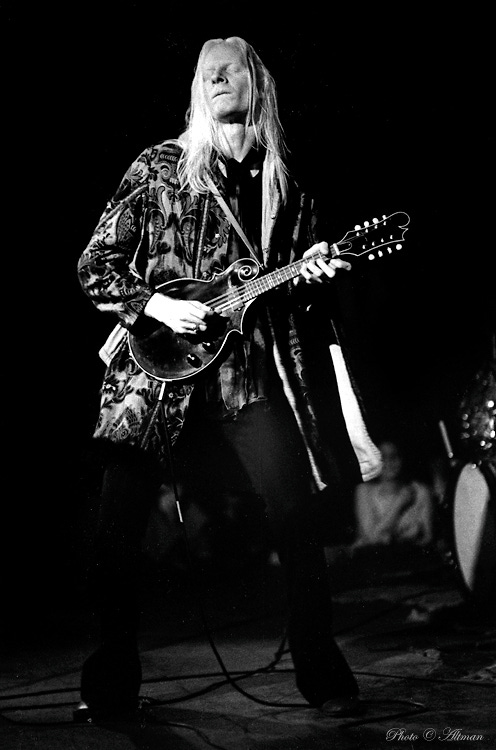

Johnny with his custom electric mandolin - anyone know who built it?

Al Kooper recalled the night (December 13, 1968) that Bloomfield brought Johnny on stage at the Fillmore East. A spontaneous spirit, Mike was constantly looking to take the music to the next level. Bloomfield loved to jam with anyone who had fresh ideas and something to say with their instrument. Secure within himself as a guitarist, Michael was a great appreciator of other musician’s abilities and talents. Both Johnny Winter and Carlos Santana found a broader audience and record contracts with Columbia thanks to their association with Bloomfield and Kooper.

“We did just two songs,” Al recalled. “One was like twelve minutes long. Within six minutes Johnny had played every lick under the sun. Michael just let him play. He was playing for his life and got his record deal [with Columbia] that night.”

Years later Johnny recalled having played an extended version of “It’s My Own Fault,” and receiving “a standing ovation” after he, Kooper and Bloomfield “blew everyone away.”

Bloomfield had previously met Winter in Chicago years before in 1962, as Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels/Electric Flag keyboardist Barry Goldberg recalled: “Michael and I were playing at this twist club on Rush Street with our band Robby and the Troubadours when this young far-out looking kid came to sit in. From the first note we knew he had the magic and super chops that blew our minds. That kid was Johnny Winter.”

“I had known about Johnny for a long time before we signed him at CBS,” Vice President of CBS/Epic Records, Lawrence Cohn said. “No one was very interested in him. He and Edgar were indelicately looked at as freaks. When folks at Epic heard I was going to sign Edgar, they made remarks about the ‘Albino book-ends.’

Larry Cohn - (photo by Kruth)

I never heard either of the brothers say anything about being white, or albino. I found them both extremely intelligent and very secure in their skin, except for eye-sight problems, which is usual for albino folks.

Johnny played occasionally at Steve Paul’s place, the Scene, on [New York’s] West Side and in England, with people like Jo Ann Kelly [the British blues singer/guitarist who died in 1990 of a brain tumor at age 46]. What changed everyone’s perception was his appearance at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East [where he appeared on January 10 and 11 1969, sandwiched between Brit-rocker Terry Reid and B.B. King]. Johnny was unbelievable, a vision, dressed in black, standing in front of a mountain of Marshall’s backed by his usual bass player and drummer.

It was a full-house, including lots of Hell’s Angels, whose clubhouse was just down the street, but were unbelievably well-behaved. Johnny tore the place up. Folks went wild and the next day, all of New York was talking about him.

“At this point CBS woke up and started talking money with Steve Paul, who was representing both Edgar and Johnny, the later preferring Columbia because of the Robert Johnson connection and Edgar, Epic and me. Apparently, he liked me and knew that I understood that he was not a bluesman. Johnny got a $600,00 advance, while Edgar received $300,000. That was a lot of money for 1969, let alone today.”

“The first Johnny Winter album I heard was The Progressive Blues Experiment not long after it came out, Winter’s bassist (for over ten years, from 1978 – 1989) Jon Paris recalled. “He was one of the best and most recognizable guitarists, whether playing slide or regular style guitar. I first saw Johnny at the Midwest Rock Festival in West Allis, Wisconsin in 1969. Johnny, Tommy and Uncle John were chauffeured to the stage in a limo. To the best of my memory Johnny played through a stack of four or maybe six Fender Twins. If somebody would’ve told me that I’d be playing with that guy in ten years, I would’ve said they were crazy!

“I met Johnny in the summer of ’78 at a club called Pop’s in New York’s East Village,” Paris recollected. “We were both there to catch Louisiana Red [AKA Iverson Minter – the Alabama-born guitarist/harmonica player] and we wound up jamming, just Red and Johnny on guitars and me on harmonica. Johnny told me he was coming back the next night and to bring my bass. I didn’t know it at the time, but that was my audition for the Johnny Winter Band.”

That August, Paris joined Johnny’s touring band, and hit the road in support of his new album White Hot and Blue, which climbed the Billboard Charts to #141.

“We never practiced,” Jon explained. “Johnny would just ask if I knew a song and off we’d go! [Jon’s hometown of] Milwaukee was so close to Chicago, I grew up listening to and loving Muddy Waters and James Cotton [with Matt Murphy]. Luther Allison was a friend, and I went to [Brew City’s legendary] Avant Garde Coffeehouse where I saw Magic Sam, Big Walter, and Big Joe Williams. Musically, Johnny and I had a lot in common - Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Eddie Cochran, Buddy Holly and Freddy King.”

Beyond the occasional self-penned tune or Dylan number (Winter’s rocking rendition of Dylan’s “Highway 61’ Revisited” is killer) or a full-tilt rave up of the Stones’ “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” Johnny’s setlist was a hearty gumbo of American classic blues and rock “n” roll. Beyond his dazzling display of chops, and the steady cookin’ boogie his rhythm section laid down, you could learn a lot at one of his shows. Winter routinely paid homage to an array of musical heroes with masterful versions of “Hideaway,” and “Sen-Sa-Shun,” by Freddie King, Chuck Berry’s “Brown Eyed Handsome Man” and “Roll Over Beethoven,” Robert Johnson’s “Come On In My Kitchen,” “Walkin’ Blues” and “Crossroads” and Muddy Waters’ “Rollin’ And Tumblin’” and “I Got My Mojo Working.”

Rob Morgan’s Portrait of JW

“The first time I saw Johnny on TV, the camera came in for a close-up and I remember thinking he had perfect hands for playing guitar,” Jon Paris enthused. “It was easy to see and hear that Johnny had excellent technique. But he could play a lot more than just great blues and rock ‘n’ roll, as anyone who’s ever heard him play [hot pickin’ numbers like the Carter Family’s] ‘Wildwood Flower,’ ‘Under the Double Eagle,’ [a favorite workout of Chet Atkins and Roy Clark’s] or [the country-flavored] ‘Ain’t Nothin’ to Me,’ can tell you. I’ve also heard him play some beautiful jazz changes.”

Playing live with Johnny, Paris’s arsenal of instruments included an early 60’s Jazz Bass (refinished black by Bob Pascoe of Milwaukee), an Inca Silver ’64 Jazz Bass and a 1962 Stratocaster. “Johnny and I would occasionally switch. I’d play the Strat and he’d play my bass,” Paris explained. “When Johnny and I switched, I might do ‘Let’s Have a Party’ by Wanda Jackson or we’d do Johnny Burnette’s ‘Rockabilly Boogie’ or Billy Lee Riley’s ‘Red Hot,’ which was a tip of the hat to Robert Gordon and Link Wray who I’d toured with before I met Johnny.

“Later on, Johnny began playing [Austin luthier Mark Erlewine’s headless] Lazer guitars and tuning down a whole step, so I put together a couple of ESP basses with heavier strings to tune down to him. Johnny continued to play slide on his Firebird [usually tuned to an open E, G or A chord] so I also brought a Hohner headless bass along for regular tuning.”

Paris not only played bass but also blew harp simultaneously in a custom amplified rack he built from plexiglass, which he used “on about half the tunes,” he recalled. “Raisin’ Cain [1980] was the first record I did with Johnny. He covered two of my tunes on that [‘Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing’ and ‘Don’t Hide Your Love,] as well as “Bon Ton Roulet” by Clarence Garlow [Johnny’s guitar teacher, from Beaumont].

Muddy Waters’ guitarist “Steady Rollin’” Bob Margolin was also knocked out by the one-two punch of The Progressive Blues Experiment and Johnny Winter. “I was immediately a fan of his amazing and creative signature guitar playing and singing and his strong performance. He seemed to me to be the best of blues and rock combined.”

Bob first witnessed Johnny live in 1969 at the Boston Tea Party (famous not only for their diverse musical rosters but also for the dazzling visuals of the Road Light Show). He returned again a year later in 1970 to discover a chaotic state of affairs – “The opening act, San Francisco’s funky horn band “the Sons of Champlin, were asked to play a two and a half hour set because Johnny was not in the building. When they finally were allowed to stop, the stage was set up, not for Johnny’s usual trio but with keyboards and another drum kit. Johnny came out with the trio and played strongly. Then he introduced Edgar, who played all the additional instruments in turn and sang great too. It was a very impressive show even though I had to wait a long time for it.

“I first met Johnny in early 1974 when he appeared on a PBS special honoring Muddy,” Bob continued. “I was already a fan of his music for five years by then. When I asked Johnny about [the Boston Tea Party show] he told me that Janis Joplin was playing at another club and he went to play with her before showing up at his own gig.”

“When I started working with Johnny, through Muddy Waters in 1976, I asked him, ‘Why the Firebirds?’ He told me that he liked the clear sound of a Fender but found them hard to play compared to Gibsons. He felt like the Firebird gave him the best of both worlds. I never played his guitars, so I don’t remember noticing anything remarkable about the way they were set up, but he used lighter strings than Muddy and I used.”

Ed Seelig of Silver Strings Music in St. Louis was more than a guitar dealer to Johnny, they were friends for over forty years. But the good times they shared usually revolved around Ed procuring another Gibson Firebird or some other exotic ax for Winter. Over the years he bought a slew of them. “They were all beautiful,” Jon Paris exclaimed.

Ed opened Silver Strings in 1972, after a couple years of trading guitars out of vans, or rented U-hauls, taking the instruments directly to artists at concerts and festivals. One such auspicious occasion was at the Galena Rock Festival on July 31, 1970… “It was actually held on a farm in central Iowa after the people of Galena [Illinois] changed their minds just two weeks before the festival, because they didn’t want hordes of filthy hippies destroying their town,” Ed said. “Johnny was playing the Fender 12-string with six strings on it, that he’d used at Woodstock as well as an Epiphone Wilshire.

(Johnny at Woodstock - Why this was omitted from the film and history I'll never understand!)

I sold him a dead-mint Firebird that night. The guy who owned it before him was a folky, who only played acoustic. I think someone in his family gave it to him because he liked the Beatles. But he hated the guitar and never played it,” Ed recalled. “I never expected to be friends with Johnny. But forty years later… We used to talk for hours,” Seelig reminisced.

One of Ed’s favorite recollections of hanging with Johnny is how he’d badgered Winter to play his National Steel guitar live, suggesting on more than one occasion that he kick off the set with a brisk acoustic rendition of “Dallas,” before scorching the crowd with his electric Firebird blues. “But he always came back at me with some excuse. He’d say he didn’t use the National live because playing acoustic was too naked and that mistakes were easily hidden with the electric guitar and his band rocking behind him. Johnny was not a real secure guy,” Ed stressed. Then there was the way Winter felt about Texas. As he sang in “Dallas” on his eponymous debut on Columbia Records:

“I load up my revolver, sharpen up my knife

Some redneck messin’ with me man, I’m bound to have his life

Goin’ back to Dallas, take my razor and my gun

Man, people there lookin’ for trouble, sure gonna give ‘em some”

“If you thought Johnny loved Texas, you didn’t know Johnny!” Ed emphasized. “They gave him such a hard time there. He got the hell out as soon as he could and never liked going back. He lived in New York City, so he could go out at night and see all the bands, and he kept a place in Connecticut. Long story short – I never got him to play the damn National,” Seelig chuckled.

One of the stranger guitars Seelig brought him over the years was a black double-neck Gibson (not the usual 12-string with a six-string neck below, but actually two six-strings). “A St. Louis local jazz player had it strung with flat wounds on one neck, which he would play jazz standards on, and on the other neck he used regular strings. Johnny thought it was a good idea to keep one in standard and the other in open tuning. You can see this guitar on the back of his Saints & Sinners album but Johnny only played once on stage as he claimed it was ‘too heavy.’”

Although much has been said about the long, lightning-fast fingers of Johnny’s left hand, Winter like the Reverend Gary Davis, worked all his right-hand magic, for the most part with just a thumb-pick.

“He did indeed,” agreed Margolin. “He could use his other fingers and play Delta Blues, thumping the bass strings, or he’d grip the thumb-pick like a flat pick and play fast, accurate, and clean. Every once in a while he’d flub a note, but he never played sloppy. His fingers were long enough to reach any standard blues lick on a Gibson. His playing seemed effortless,” Margolin marveled. “I believe that by the time I met him he had been playing so long that he didn’t think about what he was doing. He could sing anything over even complex guitar parts, and the music seemed to flow through him to his guitar and amp.”

“Johnny loved the blues and never really wanted to be a rock & roll star, not quite the way the company saw him, as they were concerned with their investment,” Lawrence Cohn said. “Johnny would rather sit and play slide on his National [guitar] or fool around with his National mandolin. Once I asked him about his use of a thumb-pick, as that’s how I played and was curious. He said he would tell me, but I had to promise that I wouldn’t repeat it. Johnny said that when he first started, he used to use a flat-pick but it always flew out of his hand, hence the thumb-pick. I told him I had the same problem and we both laughed.”

“I was floored by the onslaught of notes, but I was not influenced by Johnny’s style as much as, say Michael Bloomfield,” Dave Alvin offered. “Winter was fearless. He was fierce, and it was the fierceness of his attack that influenced me as a guitar player. While he was good technically, he made mistakes, but I loved how he’d always go for the throat.”

Inspired by Son House and Robert Johnson, Winter first slipped a slide on his pinky to evoke the sound of the Delta blues masters. Having tried a variety of test tubes and pipes, it wasn’t until he met Morris Tiding while playing a gig in Denver, that he found the perfect fit. Tiding gifted Johnny “a 12-foot piece we got from a plumbing supply place. And I’m still using that same piece of pipe now that I used back then. I just saw off another piece of it every time I need a new one,” Winter told Goldmine Magazine.

“I was never in the studio with him,” Lawrence Cohn said. “I made it a point, in most instances, to stay out, as I did not want anyone to be either inhibited or show-off because ‘The Boss’ was there. I have no idea who put together his arrangement/deal with Muddy but it was a stroke of genius.”

“It was a dream of Johnny’s to produce one of his biggest idols, Muddy Waters, and from what I understand, he approached Muddy about making a record together,” Jon Paris said. “Muddy was not into it at first, telling Johnny he’d already done his best records for Chess, but Johnny convinced Muddy (and Blue Sky Records) that it would be great. And it was, “Grammy winning” great, and there were, as you know, more cool records to follow once Muddy agreed he got excited about the project. He said ‘Johnny, I’m gonna make a great record for you even if it takes three days!’ Johnny said they completely finished the record [Hard Again] in three days!”

Bob Margolis had been playing with Muddy when Johnny joined the band and produced a series of great “comeback” albums for Waters, beginning with Hard Again which won the Grammy for best blues album of 1977.

“Muddy’s road band had two guitarists besides Muddy, and I was one of them. We also had piano, drums, harp, and bass. Johnny was our producer for the Blue Sky albums and he also played prominently and powerfully on all of them. Muddy actually never played a note of guitar on Hard Again. The band for that album was chosen by Johnny and Muddy: I was on third guitar with Pinetop Perkins on piano, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith on drums from Muddy’s band [harmonica great] James Cotton and his young bass player Charles Calmese.”

Hanging with Johnny came with plenty of highs and lows, as Ed Seelig recalled: “He loved the Bay Area!” Ed said reminiscing about Johnny’s heady days in San Francisco, jamming with Jefferson Airplane’s bassist Jack Cassidy, to sleeping on the couch at John Cippolina’s house (the legendary guitarist of Quicksilver Messenger Service). Then there was the time he went to see his friend who was secretly in rehab at the River Oaks Hospital in the New Orleans suburbs in March 1972: “I brought him a Gibson Skylark and a Les Paul. It was the only time he played in six months. That really cemented our friendship,” Seelig said. “I remember going to see him play with Muddy one night in the late seventies, in some Chicago suburb [Cary, Illinois]. That place [Harry Hope’s] looked like a 1940’s airplane hangar. The people went wild when Johnny walked through the crowd and up to the stage, carrying his Firebird. The tapes from that night later became the Muddy ‘Mississippi’ Waters - Live album that Johnny produced [and won the Grammy for Best Ethnic or Traditional Folk Recording in 1979.]”

But the combination of substance abuse and health problems that plagued him throughout his life would eventually take their toll on Winter. “Towards the end his playing was not there,” Ed confessed. “The crowds were getting smaller. I think he wanted to quit, but his manager kept him on the road, which was not good for him.”

Although he rose to great heights in his professional career, Johnny Winter, like so many before him who risked venturing down that old blues road, hit plenty of pot-holes along the way – many of his own making. His well-known proclivity for drink and drugs only compounded whatever health problems were inherent to his already frail physical condition on top of the constant grind of touring.

And then there’s the mystique and lure of the Firebird. As represented in most fairy tales, the Firebird symbolizes a journey fraught with difficulty. The hero is often compelled to take up the quest to capture the luminous creature after finding one of its tail feathers. While filled with the promise of adventure he (or she) often winds up defeated and dejected. The myth of the firebird varies from one culture to the next. Whether a mystical harbinger of doom or a sign of hope, it is often portrayed as an apple stealer (usually preferring the golden variety), and while regularly hunted, it is rarely captured. And like the Firebird itself, which Johnny will forever be associated with, he was singular, and unusual, and brought all who heard his music a sense of wonderment.

Thanks John for the delicious cocktail of info about Johnny's beginnings. I never got to see him until Sept 14, 2013, when Holly, my brother Keith and wife Bobbi and I got to see him at The Pour House, Bucks County Winery, New Hope, Pa. We were quite literally just a few feet away from the low platform stage so I had my earplugs ready. Mr. Winter needed assistance getting up to the stage but once seated and plugged in he worked his magic for a at least 1.5hrs.