From a “blindfold test” I did with Hal Willner for Wire Magazine’s Invisible Jukebox… “Cambridge, 1969” from Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions (Zapple) 1969

(John with Yoko, who had been admitted to Queen Charlotte Hospital in London on November 4th, 1968 and kept under observation. Ono suffered a miscarriage on November 21st, 1968. This photo by Susan Wood would be used Unfinished Music No. 2 Life with the Lions.)

Willner: [Begins to screech along] I could actually sing along with this for the first ten minutes when I was a kid. [More screeching and yodeling].

JK: It was always good for clearing my dorm room when I wanted my friends to leave.

Willner: Unfortunately I never played it for anyone. For me it was a solitary record. But man was it innovative.

JK: It’s still just as powerful today as when I first heard it.

Willner: Boy that just fucked people’s minds. It has a quality that I love. They don’t give a shit what anyone thinks.

(March 2nd, 1969 - John & Yoko - live at Cambridge University.)

JK: Do you remember the back of the record quoted George Martin saying “No Comment?”

Willner: Yeah. I loved the Beatles early on, but with Rubber Soul, Revolver and Pepper… um, I don’t know…Then they came back full force with the White Album. Whatever magic they had in the early years seemed to dissipate but there was a real feeling and energy to Two Virgins, Life With The Lions and The Wedding Album that culminated in the double Plastic Ono Band records.

(Yoko's P.O.B. cover photo by Dan Richter - Released December 11, 1970)

I’ve always thought of John’s Plastic Ono Band album as the greatest record of all time. As far as an honest record goes, there is nothing like it. There’s also some stuff on Some Time In New York City that’s really strong, although their relationship with reality at the time wasn’t what I would call real great. But she’s so strong. She made that record [Season of Glass] immediately after his death.

JK: Yoko is absolutely fearless. She put his bloody glasses on the cover.

Willner: And Fly was a great, great record. I loved a lot of their [The Beatles’] early solo stuff, like [George] Harrison’s Wonderwall, which I sampled and looped and used all over Weird Nightmare. Wonderwall was the soundtrack to my first experience with LSD.

JK: Well, yes, it’s really exotic and a fine choice no doubt.

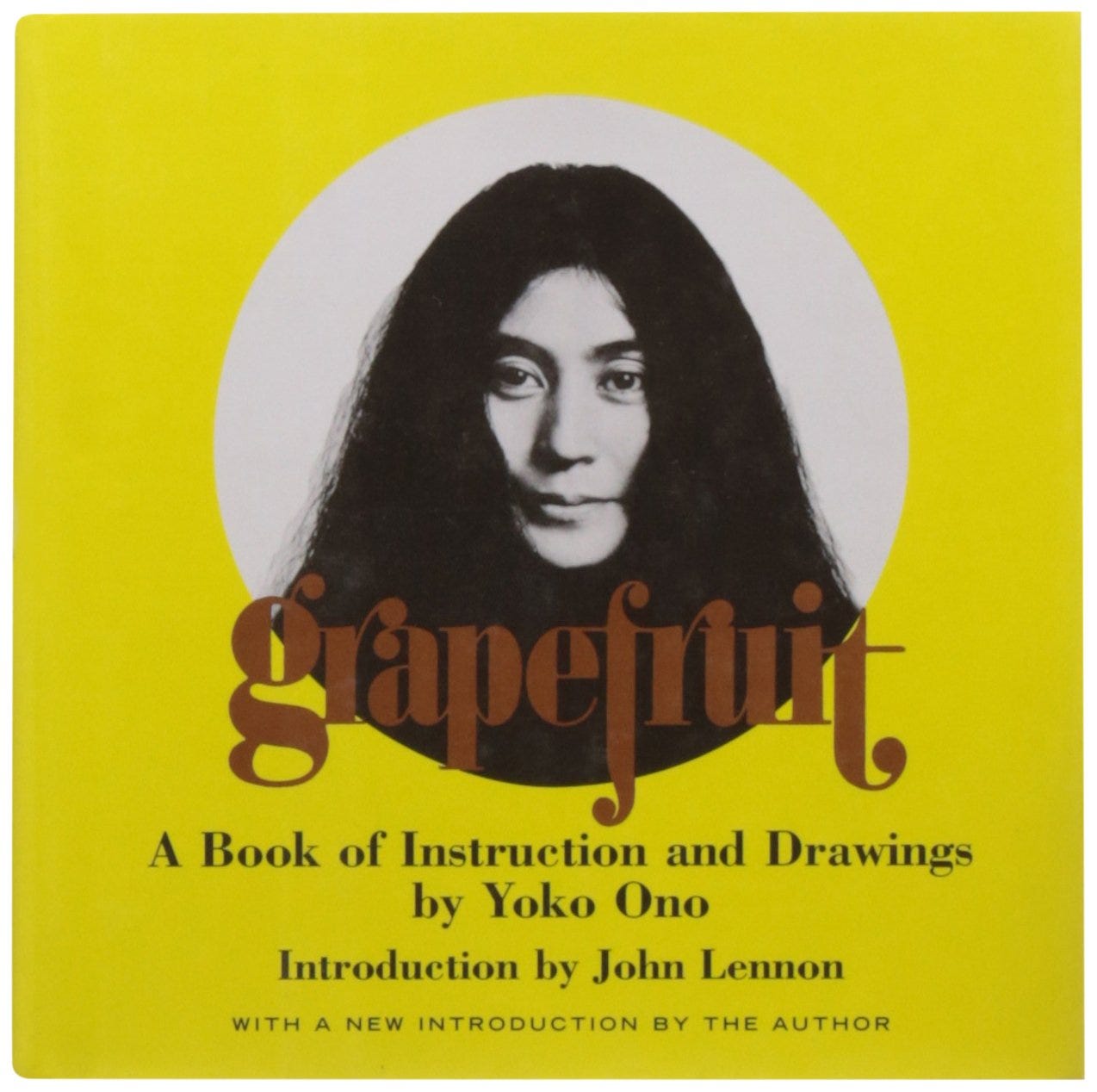

A Few Thoughts on Grapefruit…

(Grapefruit - Simon & Schuster 1970)

While grappling with reoccurring thoughts of suicide, Ono began writing the series of instruction/poems that would comprise her first book, Grapefruit, which she considered “a collection of paintings in printed form.” Ono found writing very therapeutic - “a cure for myself without knowing it,” she told journalist Charles McCarry.

Not surprisingly she couldn’t find a publisher for the book, which was eventually printed in Japan in 1964 in a limited small-press edition of five hundred copies. Grapefruit would later reach a wider audience after it was published in America by Simon & Schuster in 1971. The poems or “pieces” as Yoko termed them, were a series of evocative commands, and metaphorical recipes that, like Zen, have a powerful way of making readers think beyond the comfortable boundaries of their minds. “Line Piece,” playfully instructed readers to “Draw a line with yourself. Go on drawing until you disappear.” Although an impossible and surreal act, this radical concept was nothing new. There have been plenty of artists over the years, such as the eccentric New York painter/jeweler Axel, (AKA the “Bloody Genius”) who, whether deliberately confronting societal taboos or simply hoping to attract attention to themselves, have produced intensely personal artwork by using their own blood without facing lethal consequences.

Enigmatic and provocative, Yoko invited her readers to “Burn [Grapefruit] after you read it.” “This is the greatest book I’ve ever burned,” John later exclaimed in the jacket notes for the small, square-shaped yellow book. They were both unquestionably aware of the controversy attached to burning books, from ancient China through the Third Reich. Lennon himself had recently experienced an ugly backlash in the American South when gangs of irate fans swarmed down to local church parking lots to ignite their “Beatle trash” in big dumpster bonfires after his “Bigger than Jesus” comments in March 1966.

Like so many of Ono’s concepts, her motivation was to spur the viewer/reader/listener to reconsider their understanding and acceptance of the world around them. “Her book Grapefruit speaks for itself,” John wrote to Joe Franklin. “It is now in its fourth edition – paperback. Yoko calls them instructions to help you through life rather than poetry.”

Lennon dubbed Grapefruit “beautiful and profound,” believing its inscrutable Zen-like kōans “could help [people] to live.” In John’s not-so-humble (if not somewhat naïve) opinion, his wife was “one of the world’s most important artists.”

“Why” - the opening track of Yoko Ono Plastic Ono Band is probably my favorite, and one of the most powerful tracks she ever recorded. Not only is the rhythym section of Ringo with Klaus Voorman killin’, John plays some fantastic guitar here. And Yoko? completely off her head… gone! I often play this track in response to the increasing madness of this world.

Below you’ll find the opening chapter to the Yoko Ono section of my book

Hold On World - The Lasting Impact of Plastic Ono Band - 50 Years On (Rowman Littlefield - 2021)

“There’s a scream inside every one of us at every moment.

And every one of us has had the experience of listening to a record

and feeling that scream take over. Release. Abandon. Let it all out…”

- Paul Williams

The opening track to Yoko’s Plastic Ono Band, “Why” is just over five and a half minutes of skull-searing punk rock, recorded six years before anyone had a clue what punk was. Spurred on by John’s grungiest guitar work since “Cold Turkey,” Yoko’s terrifying screeches and screams evoke the haunted disembodied spirits unleashed in the wake of the bombing of Tokyo. Ono’s ceaseless repetition of the nagging question “Why” is similar to that of a child throwing a fit, unable to be placated no matter what answer the adult struggles to provide. Eventually “Why” transforms into a terrifying mantra embodying the cruelty and absurdity of human existence.

“John Lennon was always able to make his guitar talk. He was one of the most visceral, from-the-gut rock guitarists of all time,” said guitarist Gary Lucas, formerly of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. “But never more so than on ‘Why’ where his guitar spits lovely processed shards of metal to inspire Yoko Ono’s uninhibited caterwauling. This is some of the most radical rock guitar soloing of the era, rivaling Lou Reed’s ‘I Heard Her Call My Name,’ Syd Barrett’s ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ and [King Crimson’s] Robert Fripp on ‘Cat Food’ for sheer sonic bravado.”

Following in the wake of The Beatles’ lush melodies and harmonies Yoko Ono’s radical music seemed even more extreme and disturbing than if one somehow discovered it on its own. While “Mrs. Lennon” benefited publicity-wise from having “bagged a Beatle,” the slings and arrows of the Fab Four’s furious fans, needing a scapegoat for their recent break-up, were more than most mortals could endure. As journalist/author/musician Robert Palmer pointed out in his liner notes to Onobox (a six CD compilation box set of Yoko’s music released by Rykodisc in 1992): “It is quite likely that having John Lennon fall in love with her was the worst possible thing that could have happened to Yoko Ono’s career as an artist.”

One must wonder what the experience of hearing Yoko’s music for the first time might have been like without the looming presence of her famous husband. It is almost impossible to judge the originality and intensity of this sonic onslaught fairly without the story of their love affair entering into it. Despite John’s total obsession with Yoko and deep appreciation of her art as well as her powerful, raw vocals, she remains, to a vast majority of the public, a kook and an interloper who cast a dark spell over The Beatles’ leader.

The songs (for lack of a better term) on Yoko’s Plastic Ono Band tended to be more focused and possessed a clearer concept and sense of composition than the randomness and inherent egoism that informed much of the couple’s earlier experimental work.

Beginning with 1969’s Wedding Album it seemed that John and Yoko were purposely testing the frayed patience of even their most devoted fans. The Unfinished Music series left most people bewildered, including The Beatle’s long-time producer George Martin, who could only offer a polite, non-committal response of “No comment,” after asked his opinion of their second collaboration.

There tends to be an inherent awkwardness when artists of different disciplines (John – pop music and Yoko – primarily a visually based concept artist with a strong poetic streak) suddenly and wholeheartedly embrace a new form of expression. While Ono had musical training as a child in traditional Japanese and Western music, she was an unseasoned yet fearless performer, while Lennon’s improvisational skills were sharper when it came to cracking witty comments to the press than expressing himself with spontaneous bursts of free-form guitar. Having raised the pop song to the level of art, John initially sounded lost in the uncharted realms of avant-garde improvisation.

While something of a savant in the studio, Lennon’s bag of sonic tricks was limited for the most part to old Chuck Berry riffs and whatever shrieking feedback he could wrangle from his guitar when accompanying his wife’s hair-raising performances. Years later, Yoko admitted she hadn’t been very impressed with John’s contribution to their first collaboration, Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins. Ono complained that Lennon was “not being abstract enough… It was more like vaudeville I thought.” But John would soon find his confidence in the music, weaving jagged shards of raw sound in and around Ono’s abrasive caterwaul.

Starting with John and Yoko’s 1969 Live Peace in Toronto, Yoko, as Lester Bangs wrote in Rolling Stone, “began to show some signs that she was learning to control and direct her vocal spasms, and John finally evidenced a nascent understanding of the Velvet Underground-type feedback discipline that would best underscore her histrionics.”

Bangs deemed Live Peace in Toronto “listenable, even exciting.” All these years later, Yoko’s Plastic Ono Band stands as the most successful avant-garde collaboration she made with John, if not in her entire career. “This one will grow on you,” Lester Bangs assured his readers. “This is the first J&Y album that doesn’t insult the intelligence in fact, in its dark confounding way, it’s nearly as beautiful as John’s album.”

When Lennon and Ono turned their worlds upside down for each other over-night, divorcing their spouses (with whom they’d both grown increasingly dissatisfied) and suddenly abandoning their children (as they both had been) it was not just out of blind impulse. It went deeper, revealing a continuing of a pattern that ran in both of their families. Madly in love, Yoko’s mother Isoko Yasuda and father, Eisuke Ono, (an aspiring classical pianist who specialized in playing works by Western composers including Bach, Beethoven and Brahms, until his father on his deathbed, begged him to abandon such lofty ambitions and follow his footsteps into the world of finance) did something nearly as radical as Yoko and John - they followed their passion rather than family’s desires and married, not for wealth or social position, but for love. Well-respected in Japan, the Yasuda family was enormously rich. Attended to by a crew of kimono-clad nannies, tutors and chauffeurs, their privileged daughter would never want for anything (until the advent of World War II). There was also the matter of religion: While Eisuke’s family had adopted Christianity, Isoko was Buddhist. Ironically it was his banking career, not the dubious lifestyle of an itinerant musician, that led Eisuke away from home, to California for the first two and a half years of Yoko’s infancy, a crucial time in any child’s development. Upon her father’s return, Yoko began to fear the presence of this strict-tempered stranger and later evoked visions of Eisuke with “a huge desk in front of him.”

With war looming and anti-Nipponese attitudes steadily rising in America, the Onos returned again to their homeland before they wound up in an internment camp. Yoko, now four, attended Jiyu Gakuen in Tokyo, an elite private school where she studied piano and wrote her first compositions inspired by bird songs and various sounds of the city. By the following year, Yoko’s class-conscious mother transferred her to the elitist Gakushūin academy (originally established to educate the children of Japan’s aristocracy), where she composed her first haiku (traditional seventeen syllable poems) and created illustrations to accompany her original songs. Yoko described her mother was “a good painter,” but found her competitive and “intimidating.” Having spent many of her formative years in America, (she and Isoko and her brother Keisuke returned once more, taking a train across the country from California to New York in 1940) Exposed to American culture at a young age, Yoko was far more independent than traditionally subservient Japanese females. Different from her classmates, she spoke English, openly questioned elders, and formed her own opinions. While causing friction between them, her independence was encouraged by her mother.

Being different ultimately caused Yoko to have a “terribly lonely” childhood, eating most of her meals in silence with the hired help. Inspired by his parent’s negligence, John crowed, “They didn’t want me, so they made me a star” in his song “I Found Out.” But he might just as well have been addressing Yoko’s feelings of childhood abandonment.

After John’s murder on the evening of December 8, 1980, a shocked and bewildered crowd spontaneously gathered outside of the Dakota. A bereaved woman held a one-word sign reading “Why.” Suddenly Yoko’s 1970 recording seemed like a harrowing harbinger of the future.

While there have been many songs over the years that help soothe our weary souls in the face of the world’s hatred, violence and madness, “Why” is plainly not one of them. Yet none is more capable of capturing the sheer chaos and tragedy of such moments. This piece of sonic mayhem symbolizes man’s inhumanity to man, as Yoko repeatedly asks, demands and shrieks... “Why? why? why?” over John’s scorching guitar.

Yoko employed her voice in a similar way that Jimi Hendrix used the guitar to express himself on his interpretation of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Perhaps if Yoko had played saxophone like free jazz improvisors Albert Ayler or Archie Shepp or piano like Cecil Taylor, musicians who are still celebrated for their lasting contribution to the avant-garde, she would receive the respect she is due for her adventurous music. Lester Bangs was correct when he said whatever Yoko Ono did, she was bound to be a magnet for hatred - even if she “looked like Paula Prentiss and sang like Aretha.”

“There’s some people who believe that music is like a fashion show,” Yoko explained in a 1992 interview with Echoes magazine. “You look thin and beautiful and no blemish on your face. Some people believe that it’s actually sort of showing your guts, bringing your guts out. I’m one of those people who believe that you should really expose your heart, expose your emotion. So, in that sense sometimes my sound is not pretty.”

The --- release of Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band included an 8:41 minute extended version of “Why” that begins with John tuning up and a couple random thwacks from Ringo’s drums. John starts to twang a sinister Creedence Clearwater Revival inspired “Born on the Bayou” vamp, slashing his guitar as the band falls in and Yoko enters, shrieking like a giant radiated insect from a 1950’s horror movie. A give and take between John’s howling guitar and Yoko’s screaming ensues, creating one of the most radical listening experiences in the history of rock. The overall effect is otherworldly, as it ends with John hollering to the engineer, “Did ya get that?”

Please message me if you are interested in a signed copy of Hold on World. Otherwise you can find it on GoodReads or Amazombie!