Bright Moments - Rare Rahsaanica - Upshots and Outtakes #1

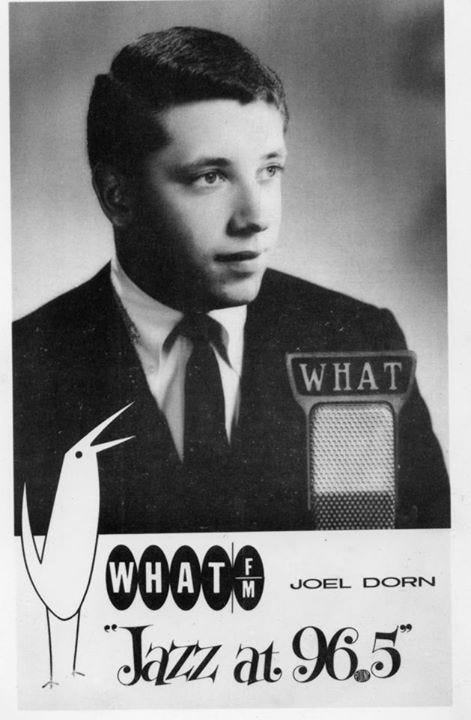

The music commonly known as “Jazz” (or as Rahsaan Roland Kirk preferred to call it - Black Classical Music) has, over the last couple of days taken some serious hits, with the passing of legendary producer Creed Taylor, WBGO DJ Michael Bourne and rising star trumpeter Jaimie Branch (just 39). Today - August 24th is also International Strange Music Day, so that trips a few triggers…. Below is an excerpt from my book Bright Moments: The Life & Legacy of Rahsaan Roland Kirk - (now in its 2nd edition) on Kirk’s 1971 album Natural Black Inventions: Root Strata - by far Rahsaan’s most radical recording to date and not surprisingly his worst selling for Atlantic Records. As well as little time spent with producers Joel Dorn, and Hal Willner (RIP) and Michael Cuscuna - thankfully still accounted for…. Enjoy!

Although in recent years it’s been touted as brilliant by New York’s downtown cutting-edge musicians, at the time of its release, this collection of stripped-down songs and improvisations was thoroughly misunderstood and worse, neglected. Here was Rahsaan in all his naked glory blowing tenor, manzello, and stritch with nothing but Habao’s tambourine and conga to accent the beat. Rough and ragged as a street busker giving it every ounce he’s got, Kirk wails the beautiful and exotic “Something for Trane That Trane Could Have Said” with a swirling stritch solo over his droning tenor. The sweet swingin’ old-timey “The Ragman and the Junkman Ran From the Businessman They Laughed and He Cried” is essentially a piano rag performed on two horns simultaneously. Rahsaan blows a walking bass line on the tenor while wailing lead on the stritch.

According to Joel Dorn, the album was recorded during a morning session, entirely live in the studio without any overdubs. Hoping to end the controversy that daunted him, Rahsaan proved to skeptics and critics alike (if they only bothered to listen) that his music was a valid expression, free of the gimmickry he was routinely accused of.

A Matter of Vibe:

Producers Joel Dorn, Hal Willner & Michael Cuscuna Recall

Rahsaan Roland Kirk

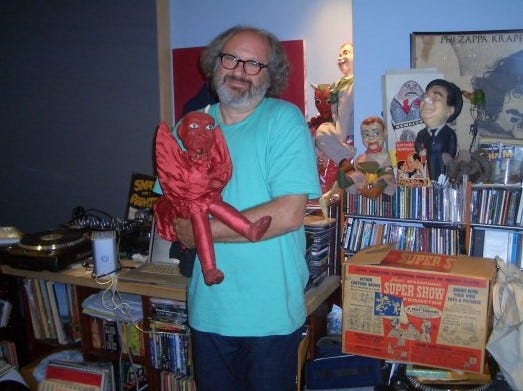

Anyone familiar with Hal Willner’s work as the mastermind behind a series of brilliant tribute albums dedicated to Nino Rota, Thelonious Monk, Kurt Weill, Charles Mingus and Leonard Cohen can immediately understand his affinity with Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Like Rahsaan, anything is possible within his ever-expanding aural universe. As a teenager, Hal grew up in Philadelphia in the late sixties, when free-form FM radio fearlessly mixed folk, rock, and jazz with comedy and classical music.

“It was a magical period,” Willner reflected, tugging at his beard, looking a bit like Rasputin in a pair of ratty high-tops. “They would play Hendrix, Firesign Theater, Dylan, Stravinsky and Ornette back to back.”

“Rahsaan wasn’t afraid to fail,” Willner pointed out. If it didn’t work out, it was no big deal; he was on to the next thing. He was the first jazz artist to make concept records. That’s why each album had a different rhythm section, a different sound. He was very concerned about the feel of an album and the way it flowed.”

Willner took issue with Kiyoshi “Boxman” Koyama’s academic, “under glass” presentation of Kirk’s complete Mercury recordings, a ten CD box set released in 1990, writing a scathing review in Musician Magazine criticizing Koyama for his sterile approach in compiling the project according to recording time and date while disregarding Kirk’s artistic vision and sense of continuity.

“It’s hard to put down a Rahsaan record,” Hal admitted. “But certain records that were little gems in their own right like ‘Slightly Latin’ were totally fucked up!”

“Rahsaan was one of the few jazz guys that thought about records in a conceptual sense. Each one was different,” Joel Dorn pointed out. “I don’t mean like Rahsaan Goes to Broadway or It’s Christmas Time Again. He had a sense of what he wanted to do. Rahsaan was way ahead of me as a musician and an original. In the beginning, I was amazed that he let me take the ride with him,” Dorn confessed. “At first I was so in awe of the fact that I was actually producing him. I’m not sure what he saw in me. As a producer, I came with training wheels. I always got off on that maybe he recognized my potential. When we first came together, he liked my enthusiasm and saw some promise in me for whatever reason,” Dorn said. “Or maybe it was just convenient,” he ventured. “One time someone close to him told me, ‘He doesn’t need you to make the records, he just needs a white boy to get in the game.’ If that was his reason - cool, I don’t give a shit, because ultimately halfway into the Atlantic thing he started to trust me and we were in tune. Before that, he wanted to control everything!”

Everything with Rahsaan was a matter of vibe. It took a few years, but eventually, Kirk began to have complete faith in Joel as his producer. “Once I had his trust, it was wild,” Dorn said with a fiendish grin. “I would say go in there and do this or that and when I played him back what I had done with it, he fuckin’ flipped. He knew I could hear like him, not as well, but I could play in the same arena. I learned how to listen from him,” Dorn admitted. “When you would call him, he would always have an instrument with him, a small one that he would play while you were talking. He’d have the television on and maybe he’d be listening to a jazz station or maybe have a record player and a cassette player on. He’d be talking to you, always fiddling with something. So he heard on that level. I can hear three things at a time. He could hear five or six!”

There is more to this last quote than meets the eye, or more specifically the ear. There is the slight matter of Joel’s hearing, or should I say, lack of hearing to be considered. When he was seven years old, Dorn caught the mumps and awoke one morning stone deaf in his left ear. His right ear didn’t fair much better. “The fact that I’m pretty well deaf might’ve appealed to him,” Dorn said cackling gleefully. “I only have about 35-40% hearing. I can’t hear stereo and I’m not able to hear certain frequencies. I realized the other day that Rah that might’ve actually seen this as a selling point.”

I knew that Joel was a little hard of hearing but I attributed this to his many years of producing records. I figured that long hours in the studio, high volume and headphones had shaved off the top end of his hearing. During our conversations, which frequently took place somewhere on the way to somewhere else, or between ringing phones or mouthfuls of sandwiches, Joel would always position himself so that he was walking, talking or chewing on my left side. This little discovery had now raised the Absurdity Factor of writing this story to a new all-time high. The idea that Rahsaan actually might’ve found Dorn’s auditory handicap appealing is incredible. The irony of a near-deaf DJ working for a radio station whose call letters were WHAT could only have been written by some crank with a sinister wit. It’s like a bad joke. Did you ever hear the one about the blind musician who made a record with a deaf producer?

“The relationship between Rahsaan and Joel was truly collaborative,” Hal Willner explained. “Most producers are just glorified engineers. Joel doesn’t operate like that. His sense of continuity was integral in creating The Case of the 3 Sided Dream In Audio Color.”

Considered a masterpiece by many, Hal has dubbed the album, the Sergeant Pepper’s of Jazz. “With that album, Joel took recording to the next level,” he said. “His use of sound effects and montage was amazing. It created this sense of surrealism which nobody was doing, especially in jazz.”

“Joel did a great job with Rahsaan although, at the time, people complained about some of the records, like Blacknuss and The Three-Sided Dream. Joel brought out the surreal side of Rahsaan’s humor and got it focused on the record,” producer Michael Cuscuna explained. “Joel had a very good relationship with Rahsaan, so I never got to make any records with him. I would’ve loved to,” Michael said, sounding a bit disappointed.

Cuscuna had also been a fan of Joel’s radio show in Philly, where he went to college. Eventually, he was hired by Dorn as a staff producer at Atlantic Records in the early seventies, after quitting his gig as a DJ on WPLJ. “It’s all very interconnected,” Cuscuna said, raising his eyebrows above his wire-rimmed glasses.

Willner had met Dorn, a DJ and a local celebrity in Philly, when he worked at his father’s delicatessen in the sixties. On one occasion he trekked all the way over to Joel’s house to personally thank him for his contribution to the music scene. In return, Dorn suggested that Hal stop in and see him whenever he got to New York. Hal got his first job in the music biz working as a gopher at Regent Studios during the recording sessions for The Three-Sided Dream.

At the same time, he was excited about meeting Kirk, he was truly petrified. “He was big and powerful and blind,” Willner said, recalling Rahsaan’s overwhelming presence. “I was scared to death of him! I literally sat at his feet the entire time. After a while, he began to recognize my voice. Then I started taking him around the city and we became pretty close.”

“On one hand, I felt I was the only person who ever should ever produce him,” Joel said. “On the other hand, I didn’t realize how weak or young I was a producer. With Rahsaan everything was a matter of vibe.”