A Belated Birthday Riff (and Spliff) to Fela Ransome Anikulapo Kuti

Or How I discovered Afro-Pop living in Berlin in the Late 1970s

In August 1993, the body of Adesanwo Shokoya was found outside Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s home in Lagos. The electrician had allegedly been beaten to death by the singer’s bodyguards after arguing over a bill for $138. Nigeria’s biggest pop star and outspoken critic of the military-controlled government was immediately arrested and charged with murder and conspiracy.

Mr. Shokoya, it seems, had been accused by Fela Kuti’s bandmates of embezzling funds. According to the police, Kuti had ordered his posse to teach his disloyal employee a lesson. But Shokoya unexpectedly died in the midst of their manhandling. While a Lagos newspaper editor considered Kuti nothing more than “a nuisance,” he clarified to a New York Times reporter that the singer was “no murderer… He’s being punished not for what he’s done, but for who he is.”

The controversial musician, whose famously blunt and accusatory remarks and decadent lifestyle made him constant fodder for newspaper tabloids, seemed remarkably unfazed throughout the whole ordeal. “It’s just another one of their ploys to trap me,” he remarked, while dressed in what the New York Times described as his “standard press interview attire - bikini underwear.” Fela, a ringmaster of the first degree, had already begun to grow weary of the circus.

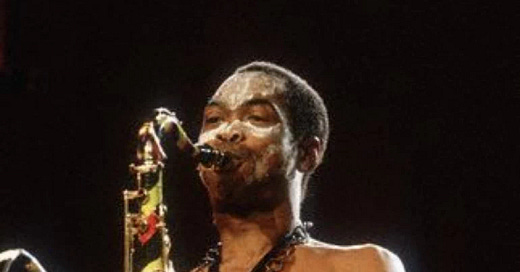

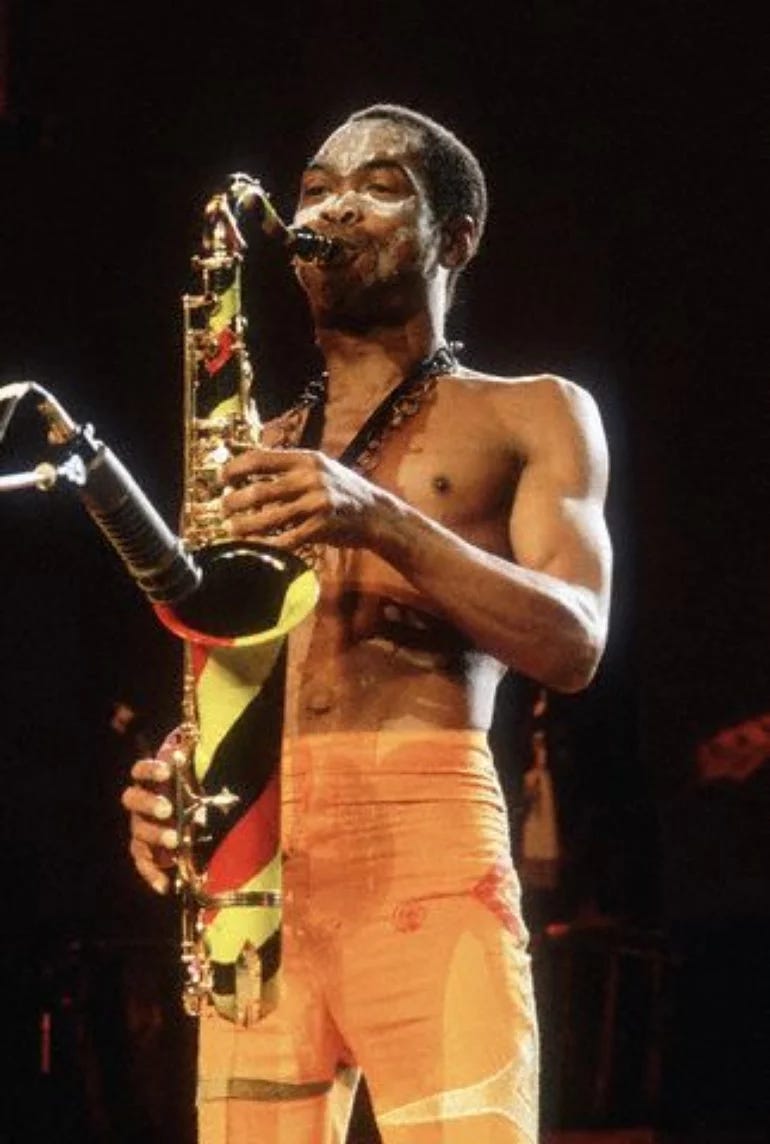

In 1974, the originator of a highly infectious style of music he dubbed “Afro-Pop,” opened the Lagos-based club called the African Shrine. As Kuti began digging deeper into his Yoruba roots, he started incorporating mystical rituals into his band’s musical performances. Archaic magicians from Ghana allegedly performed miraculous feats while shamans chanted cryptic Ifa incantations, as dancers, with painted faces and bodies swooped and twirled in zoomorphic gesticulation. A Cameroonian Priest was said to have sacrificed a man and then raised him moments later from the dead.

After meeting a young African-American woman named Sandra Isodore at The Shrine, Kuti would quickly become radicalized, devouring books by Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver, and learning the backstories of the Black Panthers’ Huey Newton, Angela Davis and Bobby Seale. Fela’s blend of volatile politics and cultural pride, which he sang of, not in his native Yoruba but in Pidgin English (in hopes of reaching a broader audience) over a James Brown-inspired funk groove, soon exploded all over Lagos.

Located across the street from the Shrine, Kuti’s musical commune he named “Kalakuta,” (after the notorious Indian dungeon known as the “Black Hole of Calcutta”) had become the constant target of police raids. Inspired by the Black Panthers attempt to establish themselves as an independent entity in the ace of what they deemed a tyrannical and racist empire, Kuti built a tall fence around his compound and declared it a self-governing state, which immediately raised the ire of the authorities.

In 1977 a squadron of soldiers surrounded Fela’s house and burned it to the ground, beating everyone inside while destroying everything they could get their hands on, including irreplaceable instruments and tapes (Kuti’s song “Unknown Soldier” recounts the entire debacle). Then came the greatest tragedy of all, a few days later, with the death of his seventy-seven-year-old mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, a well-known women’s rights advocate, from injuries incurred after she’d been pushed from a second-story window.

From that point on there was no turning back for Fela. His mounting anger could not be tamed or muzzled. Dropping his middle name “Ransome,” which he considered no more than “a slave name” Kuti adopted “Anikulapo,” which translates to “He who carries death in his pouch.” Fela likened the decision to be a powerful talisman that he wore proudly to show everyone, from the authorities to the various enemies he’d made along the way that he, alone was the master of his fate, and only he would decide when the time was right to surrender to death’s beckoning.

As his scathing criticism of the government grew, Kuti was routinely harassed by the police. Courtroom and jailhouse doors revolved with tiresome regularity. With his popularity reaching new heights, Kuti attempted to run for president in two elections in Nigeria but found his name had been kept off the ballot by his adversaries in a nefarious attempt to stop him from returning democratic rule to his countrymen.

In November 1984, Fela was arrested for carrying the sum of 1,500 British pounds while he and his band and entourage attempted to board a plane in Lagos, bound for America to play a concert tour. Convicted and sentenced to five (sometimes reported as ten) years behind bars, Kuti, who was feted as a hero by his cellmates, wound up serving only eighteen months until he was freed after General Ibrahim Babangida’s coup overthrew the Buhari government.

As legendary in his homeland as Robin Hood or Jesse James, Fela Anikulapo Kuti was not an outlaw in the traditional sense. Although he most likely carried firearms (for self-protection) and routinely instigated confrontations with the authorities, he never kidnapped anyone or robbed banks, nor, as a modern-day griot, did he sing romanticized ballads of brigands of yore. Instead, Fela continually challenged society’s norms by his example. His outrageous lifestyle, which included marrying twenty-seven women in one day (many of whom were singers and dancers in his band) and his relentless “in your face” attitude, flamboyant clothes and unrestrained radicalism, profoundly resonated with his fellow Nigerians. Kuti’s popularity soon spread to the rest of Africa, and then to London and Europe, whose youth, at the time were currently in the throes of rebellion, sparked by a devastating recession and the thrash of punk rock. Like Bob Marley before him, who found inspiration in the philosophy of the obscure Rastafarian creed for his message-filled lyrics which he fused to an irresistible beat, Kuti’s music also had the power to free people (at least momentarily) from their daily grind, and inspire them to look beyond the grim circumstances of their lives, to rise up and shake off oppression (“By any means necessary” as Malcolm X said) to create a better tomorrow.

*

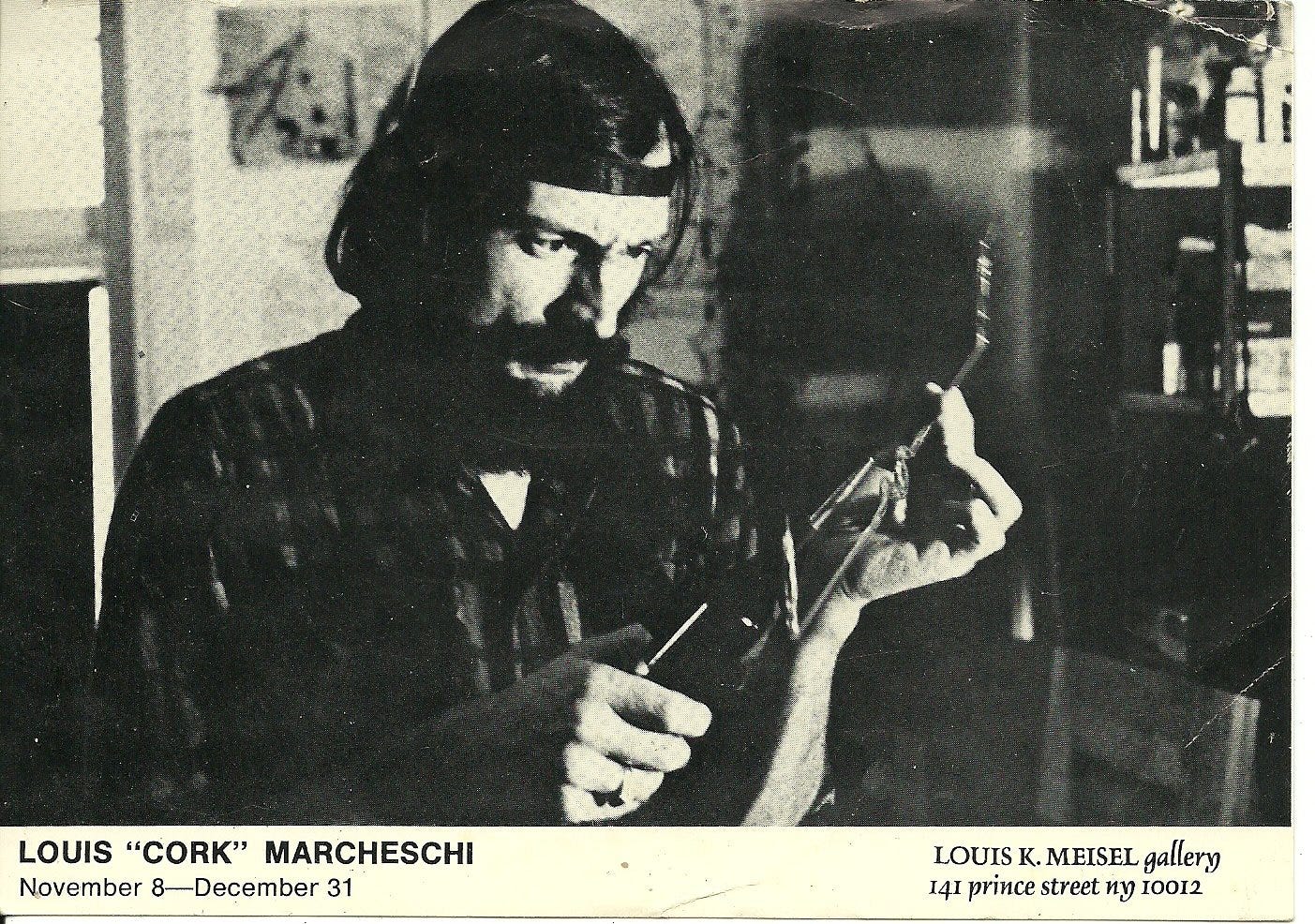

During the cold gray winter of 1978, I flew to West Berlin to briefly work for neon artist Cork Marcheschi, as his assistant, to help him install, photograph and catalog his work. A tangle of black wires and archaic hardware, Marcheschi’s sculptures sparked and sizzled with raw arcs of electricity that made your hair stand on end. They would have been at home in Frankenstein’s laboratory just as easily as in Leo Castelli’s gallery.

Cork had received a grant from the German arts program known as the DAAD and was given a studio at the Kunstlerhaus Bethanian on Mariannen Platz, just a few hundred feet from the Berlin Wall. (Sculptor Ed Keinholz had a studio there too but I stopped going by after he bilked me for twenty bucks in a hand of poker.)

The late Seventies was a wild time to be in Berlin. Punk was exploding all around the city, from fashion to graffiti, to the clubs which presented cutting-edge bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees, Suicide, and Nina Hagen (and little did I know Bowie and Iggy were in town…. They never call. They never write…)

Just beyond the shimmering electric halo of the downtown shopping area known as the Ku-Damm, lay Kreuzberg, a murky medieval village where raw slabs of meat hung in shop windows and thick coal smoke belched in black clouds from its chimneys. Wandering along Adalbertstrausse one day, I stopped in a little shop with a rainbow painted over the door called Regenbogen (Rainbow) Bazaar. Behind the counter stood a druid-like merchant with long dirty blonde hair and a pointy goatee. He was quite friendly, and his store reminded me of the old Greenwich Village head shops, back in the hippie days, when thick sweet incense filled the air.

The tiny bazaar housed an eclectic mix of cultures and styles. Its owner, Zdravko, who spoke a little bit of every language, was particularly fond of country-western music, which he listened to on the American Armed Forces radio station. Colorful prints of multi-armed Hindu gods adorned the wall. I bought a small bronze statue of Ganesh and a wood flute from India and later I discovered Zdravko had generously tossed a small hashish pipe and a bottle of jasmine oil into my shopping bag.

It turned out that Zdravko, who preferred to be called “John,” had dodged the Yugoslavian draft in 1969, only to wind up trapped in that hip prison of Western decadence, West Berlin. As he discovered West Berlin was much easier to enter than it was to leave. Nobody even bothered to check our passports when we arrived at the airport. There was no need. Surrounded by miles of bleak cement walls capped with razor-sharp barbed wire, minefields and guarded by zombie Communist soldiers toting machine guns and walking fierce German shepherds, you either left Berlin with the proper papers or in a casket.

After learning I was a musician, Zdravko invited me up to his loft that night to play “der blues.” He lived on the seventh floor of the old Leitz factory with his wife Helga and their son Marco. Their loft, which they shared with a tall British bloke named Michael, had a fantastic view of the wall and the tower on the East Berlin side. Michael built marionettes and puppets and claimed to have belonged (not sure if this is true or not…) to a London-based experimental dance group called the Stone Monkey that staged strange happenings with the Incredible String Band. Eventually, he fled to Amsterdam after the troupe was busted for hash.

The apartment was filled with a variety of instruments including a piano, an antique pump organ, kalimbas, a zebra skin drum, a couple of guitars and a wheezy ornate Indian harmonium.

After a pipe or two of fantastic Afghani hash, we improvised a long, disembodied Slavic/Indian/ British blues raga that eventually fizzled out into a bout of stoned laughter. Between pipes of strong hashish, Zdravko said he was hoping to become a citizen soon so that he and Helga could immigrate to Australia where he dreamt of “growing marijuana six meters tall.”

One night Zdravko told me he invited an African musician to stop by the loft that night to jam with us. Idowu Awe, who preferred to be called “Joe,” was a tall, ebony Nigerian from Oyo State who spoke the King’s English. He rapped briskly on the loft door three times and stood with the proud countenance of an African prince. Clad in a green leather trench coat that reached below his knee, and a knit cap on his head that resembled a British tea cozy, he greeted me with a big, bright toothy grin.

“My name is Idowu Awe and I play fantastic guitar and drums,” he announced.

“Oh, then you better come in right away,” I replied. He strode into the room like he owned the place and laid his guitar case on the kitchen table.

“You can call me Joe,” he said. “I have the finest guitar money can buy,” and popped open the latches on his beat-up case. I expected him to pull out an abalone inlaid vintage Martin or perhaps a jumbo Gibson, but to my surprise, it was a black and red Framus.

“Oh yes,” I agreed. “That’s a fine guitar indeed!”

He pulled up a chair, sat down and set his guitar on his lap. From the inside pocket of his long green leather trench coat, he produced an enormous hash joint which he planted in the corner of his mouth and ignited it.

“Oh yes, by all means…” I said. A moment later Idowu began tuning his guitar, starting with the low E string. First, he loosened the string until it was slack. Then he began tightening it back up again - boing, boing, boing. I wasn’t sure if he knew what he was doing, or if he was getting too stoned and just fooling around. I just sat there listening, watching as he tuned the strings in what seemed to be a totally random way. While the E string was tuned to the lowest pitch, the rest of the notes didn’t seem to follow any logical or conventional order.

“I tune to my head!” Idowu explained as I sat watching him in wonder. “That way every time I play the guitar, something fresh and new happens.”

At that point, I figured it was best just to listen and learn. After finally settling on a new tuning, Idowu began to chop a syncopated rhythm that I could find neither the top nor the bottom of. His eyes beamed through his yellow-tinted aviator glasses. After listening for some time, I finally picked up my flute and began to play along, slowly. Once I tossed out any rational, Western approach to music I just fell, intuitively into the groove and we played for a few hours with Zdravko and Michael eventually joining us on harmonium and bongos.

Following our jam, Idowu asked me if I’d ever heard of Fela Ransome Kuti, the “King of Afro-Pop,” a term I was unfamiliar with in 1978. And when I replied, “No,” he said, “then I will take you to see him tonight... right now!” “Fela,” he proudly announced, “is Nigerian. Just like me! This man is Duke Ellington and James Brown in one man!” I told him to “Shut up!” “You will see,” Idowu said with a Cheshire cat smile, and then lit another enormous hash joint.

Between the powerful hash and the overwhelming spectacle of Kuti and his colorful krewe (comprised of a sprawling band of dancers, horns and percussion) I can’t recall very much about the night (all these years later) other than the feeling of glee, and that I had been let in on an enormous secret that I couldn’t wait to tell my friends back home in the States.

Happy Belated Birthday Fela! And thank you for your revolutionary music which still kicks ass to this day.